THE FINE ART OF ASKING: Developing Your Deck of Go-to Questions

By Eddie Thompson

After several years working as a professional fundraiser, it’s commonly assumed that countless face-to-face solicitations will have enabled fundraisers to overcome any reluctance about asking for money. If, in a moment of honest vulnerability, an aspiring young “rain maker” admitted that he/she were terrified at the thought of making the ask, everyone would gasp for air and in the same breath whisper, “Oh, my goodness; why did you apply for this job anyway?” Then we veteran fundraisers would huddle around like old sages to offer our best advice.

Before making my own suggestions, let me say that in my early years I was terrified asking for money, particularly for major gifts. Coming from a middle-class background, it was difficult for me to imagine a donor making a $5,000 contribution, let alone a five to seven figure gift. Those first asks were characterized by such nervousness and insecurity that it’s a wonder that anyone contributed at all. I think a lot of donors agreed to give simply because they felt sorry for me.

The fear of asking can be paralyzing, a feeling most new fundraisers have to overcome. If they stick with the profession, grow in confidence, and advance in their careers, the asks will get larger and more diverse—major gifts, capital campaigns, endowments, planned gifts, etc. They’ll have to deal graciously with some demanding donors, aggressive funding goals, and a lot of “no’s.” The challenges to step-up and step beyond one’s comfort zone are never-ending and ever increasing. So, the greatest fundraisers think of overcoming the reluctance to ask as an evolving process rather than a point-in-time accomplishment.

Those first asks were characterized by such nervousness and insecurity that it’s a wonder that anyone contributed at all.

INITIAL CONVERSATIONS ABOUT GIVING

Like most fundraisers, I’ve picked up some tips along the way—approaches that take the awkward edge off the simple asks. And over the years I’ve collected a battery of go-to questions to start conversations about giving. Here are a few:

When and how did you get involved with our organization / hospital?

That’s a good question for new fundraisers meeting with existing donors. Giving history for a particular donor is easily retrieved. Understanding WHY they started giving is far more significant.

How did you find out about our organization? Was it through a friend, your work, etc.?

Nothing is more important than identifying and thanking your organizational advocates. That question will inevitably lead you to an individual who has rarely donated but is, nonetheless, an advocate for your cause.

When and how do you make your giving decisions?

Grant-making foundations have set times and criteria for funding requests. It is, of course, a lot less formal with individual donors. However, that doesn’t mean they don’t have a process, and if you’re unaware of their criteria and timeline, your organization will miss a lot of funding opportunities from individual donors.

How do you evaluate your previous gifts?

Wise fundraisers take notes and follow-up with major donors based on how they evaluate their giving.

Perhaps, some of those gifts were to your organization, which leads to the obvious follow-up:

Why was it so rewarding to you and/or how could we have made that a more meaningful experience for you?

YOUR BEST STORY

I’m always looking for new ways to initiate meaningful conversations with donors. They’re like playing cards that I hold in my hand and play at critical moments in the game. The more I collect, the easier donor conversations become and the more likely they are to agree to future visits. If you’re not a serious collector of reasons to give, organizational stories, or conversation starters, it’s like “playing without a full deck.”

A recent addition to my deck of conversation starters was suggested by one of my associates. One of his favorite go-to questions is:

What’s your best personal or family story?

My associate assures me that some of the most comical, inspiring, or poignant stories he has ever heard have been responses to that question. It seems to work much better than the general, “Tell me about yourself,” or “What are your core values?” Those leads sound so very transactional. That card (i.e., question about your best story) has to be played at the right time with the right people, and it’s not a question about giving. Nonetheless, it often reveals important things about a donor’s motivation and serves as a point of connection. My associate went on to share an example.

“The last time I asked that question, we had a couple visiting with five boys in the family. ‘What’s your best family story?’ I asked the boys. There was no immediate response, and so the conversation continued to stumble along. About five minutes later, all the boys began to talk as one after another they told their best stories. I was able to make a remarkable and unforgettable connection with that family.”

INTERVIEW WITH INDUSTRY ICON

Several months ago, I interviewed Jodi Davis, Chief Philanthropy Officer for Sutter Health in Sacramento, CA. She referred to some of her favorite go-to questions when trying to initiate meaningful conversations with potential donors. She identified two of her favorites.

What’s been your most rewarding giving experience?

What’s been the least satisfying experience?

Recently, Jodi posed those questions to a potential donor who replied, “I’m not really a donor; I don’t give a lot.”

Jodi could have ended the conversation right there but decided to press the question a little further.

“When you have given,” Jodi asked, “what was the most fulfilling experience?”

The lady who had been active as a volunteer paused for a few moments and replied, “Wow, no one’s ever asked me that.” Finally, she described a gift that she made to her church and why it was important to her. They talked together at length about the importance of that gift. This was a person with the means and the motivation to give. Jodi counted it as a successful donor conversation because it actually helped the donor begin to see herself as a philanthropist who was indeed making a difference.

I AM A PHILANTHROPIST

A subtle but important aspect of these types of questions is that they assume the best about current or potential donors—that they are already generous givers, or at least, they would like to be. It’s hard to overestimate the power of positive affirmation. If you see others with eyes of faith, it will eventually change the way they see themselves.

A subtle but important aspect of these types of questions is that they assume the best about current or potential donors—that they are already generous givers, or at least, they would like to be.

It can also change the way fundraisers think of what they do. Early on in my career as I was making one of those nervous presentations that sounded more like an apology than a funding appeal, a donor replied, “Eddie, don’t ever be ashamed to ask people to give to a noble cause that you truly believe in.” Obviously, I was far more nervous about asking than he was about being asked or about giving. That brief exchange became a giant leap forward in my self-perception as a fundraiser. I determined to no longer see myself as simply working in the area of philanthropy, I WAS A PHILANTHROPIST (literally, “lover of mankind”). It wasn’t because my contributions to the organization put me into that major-donor category. It was the result of a new life orientation—as if the balance had suddenly shifted. I began to identify with the mission of that charity more than I did the process of raising money for it. Fundraising is simply my way of helping.

REIMAGINING YOUR OCCUPATION

In the succeeding years, I’ve learned that time and experience DO NOT automatically overcome a deep-seated fear about repeatedly asking for significant sums of money—sometimes at great sacrifice to the donors. My suspicion is that there’s a lot more reluctance about making the asks than long-time career fundraisers are willing to admit. The next time someone asks you what you do, you can say as you always do, “I’m a fundraiser for XYZ nonprofit.” Or, you can try this response: “I’m a philanthropist championing causes of people in great need.” I like the sound of that because it fits how I want to see myself as a fundraiser.

____________

Eddie Thompson founded the unique Thompson & Associates process in 1996 (then, under TrustMark Charitable Strategies) and later incorporating as its own entity in 2005. As CEO of Thompson & Associates, Eddie provides leadership and direction to over 35 seasoned charitable estate planners with an inspiring sense of generosity, integrity and passion for helping others.

Eddie serves as the Chair of the Charitable Estate Planning Institute, a 501(c)(3) public charity offering top level education on charitable estate planning for development staff, gift planning officers and professional advisors.

IMPOSSIBLE SHOT: Impact of Unrealistic Fundraising Targets Passed Down from Above

By Eddie Thompson

I have a lot of conversations with nonprofit professionals at all levels—from foundation presidents to major gift officers to fundraisers in their first development jobs. Among the most frequent stress points I hear almost every business day are fundraising goals being passed down from senior institutional executives who are not directly involved in donor relations, new donor acquisitions, or other aspects of the overall fund-development process. This month’s post is a brief discussion about those funding mandates and their potential effect on fundraisers and donors.

Fundraising Targets Driven Primarily by Organizational Need

Pressure from outside the development department that gets passed down to the fundraisers is often a function of organization need rather than an accurate assessment of the capacity and willingness of the donor base to give. A subtle but very real aspect of fundraising is that whenever fund development is driven primarily by organizational need, it inadvertently becomes less and less donor-centered—but, rather, more and more organization-centered. Over time, development professionals can become so focused on mandated goals that they are only minimally concerned about whether or not the amount or the structure of a gift is in the best interest of their donors. The more hardened fundraisers consider that to be the responsibility and the problem for donors, not fundraisers.

Whenever fund development is driven primarily by organizational need, it inadvertently becomes less and less donor-centered—but, rather, more and more organization-centered.

Very rarely do development professionals start out that way but after a few years of high pressure, need-driven fundraising mandates, their approach is far more transactional and far less donor-centered. If that becomes your professional profile and if organizational need is the primary factor driving your fundraising, then donors (particularly experienced donors) will spot it almost instantly. It becomes most noticeable when fundraisers are under pressure to meet funding goals, and in turn, pressure donors to give big, to give cash, and to give now.1

Emotional Account Balance

Regardless of where they originate, realistic fundraising goals cannot be established apart from the organization’s investments in long-term relationships. The Emotional Bank Account Model first appeared (as far as I know) in the leadership classic by Stephen R. Covey, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People.2 Every time an organizational representative makes a direct appeal for a gift, he/she is making a withdrawal from the relationship account with that donor. Too few significant deposits with too many significant withdrawals, and the balances in those accounts can run very low.

When balancing a checkbook in your head, most of us typically underestimate the number of withdrawals and, therefore, the available balance in the account. The same is true with donor relationships. We tend to over-estimate the meaningful deposits and underestimate the impact of appeals for sacrificial giving (the withdrawals). You may have had the painful experience of suddenly discovering that the emotional account with a particular donor was overdrawn. The donor was not nearly as committed to your cause or in love with your organization as you had imagined.

Every time an organizational representative makes a direct appeal for a gift, he/she is making a withdrawal from the relationship account with that donor.

A recurring theme in most of my blog posts is the priority of having regular and meaningful conversations with donors. As I have said on numerous occasions, “The more conversations you have with donors and the more asks you make, the more money you will raise.” On the surface, the “more appeals equals more money” approach seems contradictory to Covey’s Emotional Bank Account model. However, the solution is not to ask less (make fewer relationship withdrawals) but to make a lot more significant deposits. Christopher Dollard writing for the Gottman Institute: A Research-Based Approach to Relationships3, cites the institute’s key to healthy, productive relationships be a 5:1 ratio of investments to withdrawals in each emotional bank account—a good rule-of-thumb for nonprofits to measure the strength of their donor relationships.

Donor-conversation Strategies

Most fundraisers would love to have more meaningful conversations with those who are funding their organizations, and they love the idea of cultivating long-term relationships. Some, however, consider investments required for all those visits and conversations to be quite expensive and very idealistic. One of the most common push-backs I hear from fundraisers is that they have difficulty scheduling meetings with donors. That didn’t start with Covid-19, but the pandemic has certainly made it more challenging. Donors rarely say to fundraisers, “Hey, you’re overdrawn in your relationship account.” Most are too busy or too considerate for those kinds of unnecessary confrontations. However, nonprofit representatives will begin to see signs of overdrawn relationship accounts with donors when they attempt to set up future meetings. It’s usually not the current request but the previous conversations that create donor reluctance.

One of the most common push-backs I hear from fundraisers is that they have difficulty scheduling meetings with donors.

I have three primary objectives for each donor conversation. 1) I want them to learn something; 2) I want them to feel something; and 3) I want them to do something great. That’s been my strategy for 40 years, and I’ve found that to be most productive.4

Below are a few questions I repeatedly ask myself about my visits and conversations with donors.

How prepared am I for each donor conversation? Or am I just working down through my contact list, looking for someone willing to meet with me?5

Does the conversation focus on information they’ve heard a dozen times, i.e., the same old story?6

Do I talk to donors only when the objective is to secure an immediate gift?7

Am I straightforward about the health of the organization or is it a thinly veiled PR message?8

Am I sincerely donor-centered or just trying to bag another donation?9

How good am I at listening and creating two-way conversations?10

Am I talking at donors or talking with them?

These are just a few of the questions I’m constantly asking myself because if my approach becomes more superficial, organization-centered, and/or transactional, it would not at all be surprising if donors were increasingly reluctant to meet with me.

Managing Donor Relationships

Two fundraisers showed up at my office several years ago announcing the sizable donation they had determined I should make. I had never heard of the organization and had never met either of them. That is to say, they had no relationship account with me. The conversation didn’t last very long. As politely as I could, I stood up, ended the conversation, and asked them to leave. Donor fatigue is not necessarily fatigue in terms of actual giving but fatigue in being pursued by fundraisers when those fundraisers have not cultivated the depth of relationship to do so.

Alexandra Pia Brovey, J.D., LL.M. is a leader and experienced charitable gift planner. Currently, she is the Senior Director for Gift Planning at Northwell Health Foundation in New Hyde Park, New York. Here’s a brief quote from a conversation I had with Alex for our podcast series Conversations with Industry Icons.11

Donor fatigue is not necessarily fatigue in terms of actual giving but fatigue in being pursued by fundraisers when those fundraisers have not cultivated the depth of relationship to do so.

“I would say my biggest mistake early on as a fundraiser was trying too hard to [schedule] personal visits or phone conversations. I’ll never forget the mistake I made with one couple. I had tried to contact them five or six times. My heart kept telling me to stop, but my brain kept telling me to press on. When I finally, ‘caught them’ at home, the potential donor said, ‘We got all your messages, cards, and e-mails, but this time, you got us.’”

The implication was that the potential donors successfully avoided the call until they let their call-screening guard down and were “caught.” Alex concluded the story, saying:

“If you push too hard, you can easily topple things, and then you’re in a worse situation than if you waited for better timing.”

Inexperienced fundraisers don’t always have the experience (emotional or relational intelligence) to accurately judge the depth of relationship required to make significant appeals. I made the same mistakes early in my career, not due to pressure from above but simply out of insecurity. I was simply trying to prove my worth to the organization by pressuring donors to give.

Redefining Donor Fatigue

The most stressful and emotionally taxing relationships in your life are those without established boundaries. With the ease of electronic communications, my efforts to restrict the barrage of promotions and solicitations is something donors (myself included) have to do every single day. My experience has been that donors don’t like unpredictable or unmanageable relationships. Consequently, it was my habit to do whatever I could to make visits and appeals predictable and manageable. In other words, I created predictable boundaries in the donor relationships I had cultivated.

My experience has been that donors don’t like unpredictable or unmanageable relationships.

I outlined my donor cultivation process on my 12-foot roll of butcher paper and followed that for my entire career. Since many of you have heard or read my account of that process12, I’ll briefly summarize.

In the first quarter of each year, I visited my A-list donors, updated them on the organization’s victories and challenges, explained how their donations were being used and discussed what their gift commitment would be for the current year. I hand-delivered their tax receipt, expressed my sincere gratitude, and followed up the meeting with a handwritten note. I repeated the same process with my B-list in the second quarter, C-list in the third, and finally the D-list donors. Throughout the year I would make additional calls and/or send more handwritten notes. I would schedule follow-up visits when I sensed any hesitation.

A personal note: If a fundraiser knew what an easy target I was for being sincerely, personally thanked and appreciated, there is no telling what the organizational representatives could get me to do for them—only by asking.

TAKEAWAYS

There are four simple things to remember from this brief post.

1. Don’t show up for donor visits unprepared.

2. Unrealistic funding goals often force fundraisers to be far less donor-centered, far more transactional, and much more likely to transfer that pressure to donors.

3. The goal is not to simply make fewer significant withdrawals but to make many more significant donor relations deposits.

4. Fundraising goals are a function of cultivating donor relations, not the reverse.

____________

THE PHILANTHROPIC APPROACH: What Nonprofits Accomplish that Government Funding Never Can

By Eddie Thompson

Last month’s article was about donors’ decisions to invest their social capital (contributions to community and society) by means of estate gifts to charity rather than the government in the form of taxes. It’s not that all government-funded programs are hopelessly inefficient, though there are plenty of examples of politically motivated spending or waste that is beyond comprehension. As said last month, “When it comes to strategic applications of funding to solve big problems, one essential fact stands out: the more politicized the process, the less focused the attempted solution.”

This month I want to move on from the question of EFFICIENCY to say a few words about the potential E

FFECTIVENESS of philanthropy to solve systemic problems. Below are some of the reasons that government is either unable, ill-equipped, or simply unmotivated to effectively address the biggest social problems of our day. I will also share a few thoughts about the best practices of highly successful fundraisers.

1. The philanthropic approach to problem-solving has no financial limitation. Giving to a great cause is highly contagious. Word gets around and attracts other donors. One lead gift and/or one passionate donor can become an avalanche of philanthropic commitments.

Children who have been traumatized by mental and physical abuse typically see a physician for 20 to 30 minutes. The mission of the Blank Children’s STAR Center in Des Moines, Iowa (formerly the Regional Child Protection Center) is to work as a team with experts in child health, development, and welfare to provide services and support to children. The long-term objective is to increase a child’s resiliency and restore their health and well-being. The STAR Center houses a Child Advocacy Center and three specialized clinics designed to meet the needs of children and their caregivers.1

PHILANTHROPIC APPLICATION: Thompson & Associates doesn’t serve as organizational fundraisers. We exist only to assist with the estate planning needs of our clients’ donors. That being said, donors in the Midwest region have repeatedly expressed their eagerness to make major gifts to the STAR Center—gifts of cash and testamentary bequests, as well as one very large future gift in a donor’s estate plan. That same dynamic is true at other organizations that serve children in need. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, TN attracts donors like mosquitoes to a bug light. What can touch potential donors’ hearts more than a sick or abused child, especially donors who have had that experience themselves? St. Jude has a unique operating model. In the years ahead, an estimated 87% of the funds necessary to sustain and grow St. Jude will be raised each year from generous donors who have joined in a common cause: Finding cures. Saving children®. 2

2. A philanthropic approach is not only decidedly optimistic, it is the one form of funding that can be decidedly multigenerational. In 1785 the French mathematician, Charles Joseph Mathon de la Cour, wrote a parody of Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanac in which he mocked Franklin’s unbearable spirit of American optimism. The Frenchman fictionalized about “Fortunate Richard” leaving a small sum of money in his will to be used only after it had collected interest for 500 years.

Franklin, who was seventy-nine years old at the time, wrote back to de la Cour, thanking him for the great idea and telling him that he had decided to leave bequests to his native Boston and his adopted Philadelphia of 1,000 British pounds to each city on the condition that it be placed in a fund that would gather interest and support the public good for the succeeding 200 years.

A philanthropic approach is not only decidedly optimistic, it is the one form of funding that can be decidedly multigenerational.

PHILANTHROPIC APPLICATION: Systemic problems are not solved quickly and almost always require a long-term commitment, combined with a trial-and-error approach. Charitable trusts, Donor Advised Funds, and endowments are typically set up to support charitable causes for generations if not in perpetuity. In contrast, government funding from local, state, and federal agencies is typically assessed annually (or at least triennially) and requires a repeated approval process. Every time the political winds shift, government funding for many essential programs is on the chopping block.

3. Philanthropy is uniquely innovative. Two years ago, we worked with a gentleman on an estate plan that created an extraordinarily large gift. As a major donor to a hospital foundation, the donor was acutely aware that one of the major challenges for regional hospitals is recruiting and retaining highly qualified doctors and nurses. There were far more opportunities for career development in big cities.

Strategic philanthropists are less likely to donate tactically to fix a single problem nor do they give emotionally to simply create a feel-good moment. It’s not that they’re uncaring or unwilling to respond to a particular need. Rather, their compassion and response to needs are expressed in large strategic gifts that focus on fixing systemic problems.

PHILANTHROPIC APPLICATION: Our client-organization’s donor will make a dramatic difference with a major gift to fund a continuing education facility used for advanced training of physicians with a simulation lab for doctors and nurses. In this case, the donor attacked a regional problem at the source. The facility is up and running and beginning to equip medical professionals to become experts in their respective specializations.

Generally speaking, local problems are best served by local leaders who innovate and adapt to the specific needs of the people they serve. Government-funded programs by law must treat every population segment and every locality the same way. Consequently, creativity, experimentation, and innovation are prohibited. Those innovative solutions are usually the result of a philanthropic approach.

The inflexible bureaucracy and restrictions on the use of government funding are often the source of mission paralysis. Adaptability is painfully slow if even at all possible. On the other hand, philanthropy can quickly adapt to situations on the ground (as nonprofit leaders say) “at the speed of need.”

4. Philanthropic approach to systemic problems often challenges the institutional status quo. A lot of money has been pumped into various social and educational programs over the last several decades. If, however, government-funded programs provided workable solutions to poorly performing schools, multi-generational poverty, drug addiction, or homelessness, the problems would have been solved long ago or at least showing a significant improvement. Instead, there is a negative feedback loop that has people trapped in those unfortunate situations. One problem feeds another problem that feeds another.

Government-funded programs by law must treat every population segment and every locality the same way. Consequently, creativity, experimentation, and innovation are prohibited.

One example: less than 5% of the world’s population lives in the United States. Yet, one out of every five prisoners in the world (20%) is incarcerated in the U.S.3 The prison population in the U.S. is greater than the number of prisoners in China and Russia combined. The Bureau of Prisons (BOP) happens to be one of the most politicized agencies of the federal bureaucracy. Candidates for public office compete to be the toughest on crime until it becomes so incomprehensibly draconian, candidates are put on the spot and forced to promise to make reform… which are quickly forgotten.

Prison Fellowship, the nation’s largest Christian nonprofit serving prisoners, former prisoners, and their families, was founded in 1976 by Charles Colson, a former aide to President Nixon who served seven months in federal prison for a Watergate-related crime. It’s worth noting that in the U.S. all felonies are considered crimes against the state (not against individuals). While judges have the prerogative to punish crimes by ordering some form of payment to injured parties, it rarely happens. The goal of our criminal justice system is almost always punitive.

The Faith & Justice Fellowship (a division of Prison Fellowship) is a leading advocate for criminal justice reform, advocating a just process, proportional punishment, and (most importantly) a chance to make amends. Instead of warehousing convicted felons and branding them with a mark that they will carry for the rest of their lives, restorative justice compels responsible parties to make up for their harms. This faith-based organization creates a pathway to restitution, redemption and reconciliation with the community.

PHILANTHROPIC APPLICATION: The programs of Prison Fellowship are highly effective and far too numerous to mention. No matter how successful, challenging the status quo with innovative nonprofit ideas is usually a surefire way to stir up opposition. But because the need is so great and the systemic problems are so quickly growing, Faith & Justice Fellowship advocates are making extraordinary impacts on one of the most pervasive problems in our country. Christian initiatives are not always welcome in places that house hardcore criminals. However, Prison Fellowship’s program and message have inspired personal transformations in ways that generic 12-Step programs have not. It’s a mission that could only exist as a philanthropic initiative.

WHAT THE BEST ORGANIZATIONAL FUNDRAISERS DO

It’s hard for professional fundraisers not to think about their donors in terms of their donations. I can assure you, however, that donors rarely see themselves in that context. They usually think of themselves as husbands and wives, parents or grandparents, Little League coaches, investors, businessmen, hunters, fishermen, season-ticket holders, or club members. For most donors, giving is an afterthought. It’s not that they are stingy or self-absorbed, but giving is the one thing on their long list of financial, family, and vocational concerns that they have no obligation to attend to. Consequently, you cannot expect all donors to be innovators, multigenerational thinkers, or strategic philanthropists.

Donors usually think of themselves as husbands and wives, parents or grandparents, Little League coaches, investors, businessmen, hunters, fishermen, season-ticket holders, or club members. For most donors, giving is an afterthought.

Nonprofit leaders cannot wait for major donors to formulate a strategic giving plan. The leaders must cast vision, inspire donors with a dream, and convince them that all things are possible. They need to paint a picture of the preferred future that is so detailed, so effective, and so enticing that it captures donors’ imagination and keeps them up at night thinking about it. Fundraisers need to take the initiative to plant and cultivate the seed of multigenerational, innovative, and strategic philanthropy.

____________

Fundraiser Fatigue:

Maintaining Romanticized Optimism About Your Profession

By Eddie Thompson

In my many discussions with fundraisers over the last nine months, one of the most frequent comments has been: “We’re so weary of talking about the Covid-19 pandemic and its ongoing impact on charitable giving.” That underlying anxiety (spoken or not) is magnified not only by the resurgence of positive tests and hospitalizations but by the uncertainty of when (if ever) things will return to a normal fundraising environment.

Among the best fundraisers, it’s not so much related to job security but to the constant frustration about their inability to do the things that they know will help fund the organization. They are, of course, concerned about their own financial security for their families, but not far behind is their passion for the institutional mission. Most fundraisers are mission-oriented, championing the cause of those in need.

The good news is that in my conversations with major donors, generally speaking, donor fatigue is far less prevalent than the corresponding fundraiser fatigue. There may be some who are hesitant to charitable giving, but the vast majority are as enthusiastic as ever about the organizations they have traditionally supported. In fact, estate-planning conversations with major donors show even greater interest in planned giving.

The good news is that in my conversations with major donors, generally speaking, donor fatigue is far less prevalent than the corresponding fundraiser fatigue.

Development professionals are on the front lines, standing in the gap for the needs of people in our communities. I’d like to encourage those who have chosen the noble occupation of fundraising with the thoughts that follow.

NOBLE OCCUPATION

The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was published in 1606. The Spanish classic follows the adventures of a nobleman who (under the assumed name, Don Quixote) set out to revive chivalry, bring justice to the oppressed, and right the many wrongs of his day. In the story, people typically made fun of Saavedra’s fictional hero because he didn’t see the world as they saw it. Don Quixote perceived himself as a man on a mission, a knightly quest to become the champion and defender of all who were in need.

The most effective nonprofit leaders I’ve known are those who have been able to maintain a kind of romanticized ideal about their occupation. That’s not always easy to do. Many at-risk kids are overcome by their risk factors, and the dreams of promising students don’t always come true. Contending with unrelenting needs as well as the occasional setbacks over time can wear down one’s enthusiasm. Nonetheless, the best fundraisers somehow find ways to remain optimistic and idealistic. In other words, the best fundraisers have a little bit of Don Quixote in them.

One of our associates told me about a similar individual—a chaplain at a juvenile correctional institution where he once worked. The chaplain was one of those irrepressibly optimistic leaders. In contrast, many of the institutional staff had grown cynical after a few years of working with kids with long criminal records and habits that were hard to break. Like Don Quixote’s critics, the correctional officers frequently made fun of the chaplain’s teary-eyed compassion and (what seemed to them) his irrational optimism.

I’ve known many great fundraisers over the years. Two from Iowa come to mind.

Charlie Becker founded Camp Courageous, an amazing summer camp near Monticello, Iowa, that serves special-needs children and adults. These individuals and their families face significant challenges every single day. Go on a tour with Charlie, and he would still tear up telling you about Camp Courageous. It was hard to resist his passion for the people he served. Charlie is now retired but as passionate as ever about the mission of Camp Courageous.

Don Ireland-Schunicht has been at the same children’s hospital in West Des Moines for 40 years. When he starts talking about what they do for patients, you get that same feeling. He’s on a life mission, championing the cause of kids facing serious medical issues. Don tears up sometimes also, but being a great fundraiser is not about tears. These two guys are much more than fundraisers. They’re fully engaged with their own noble causes.

The irony is that these men seem to be more focused on the mission than on the money, the result being that donors line up to give generously.

SELF-PERCEPTION AS A CAREER FUNDRAISER

Nonprofit executives (fundraisers in particular) are constantly making the case for their organization’s mission. If you do something enough, it’s hard to keep from becoming quite good at it. However, as a career fundraiser, the first and most important case is the one you make to yourself. Have you convinced yourself of the worthiness of your cause and career choice? Do you believe it’s important enough to put yourself out there in the role of a solicitor, constantly asking people for money? If you don’t make that case and win that argument with yourself (and win it convincingly), there will be a ceiling to how successful you can be in this line of work. That’s as true for seasoned veterans as it is for rookies.

It’s easy to feel good about yourself when your occupation is being validated by enthusiastic donors throwing money at you. However, somewhere buried in the recesses of your mind, there may be an unresolved issue. Deep down there lurks an image of yourself as a beggar on the street corner with cup in hand. It’s in hard times when that inner image begins to reveal itself—like when your ten best donors are unmoved by your latest appeal and show signs of losing their excitement for your organization. It’s in the face of those difficult situations that a weak case for the value of your occupation begins to surface. That’s when you have to fight the battle of self-perception. If that’s your situation, never give into becoming one of those task-oriented cynics like the chaplain’s critics at the juvenile correctional institution.

As a career fundraiser, the first and most important case is the one you make to yourself. Have you convinced yourself of the worthiness of your cause and career choice?

A GRADUAL PROCESS

If I believe in a cause and have properly cultivated the relationships, I have no hesitation about asking donors to give with extreme generosity. But that wasn’t always the case. At the beginning of my career, it was inconceivable to me that people would make the kind of donations that I now see regularly. With time and experience, my confidence grew, and I got much better at asking for money. However, a seminal moment in my own professional development came with the loss of our infant grandson and my own son’s subsequent challenge to me. See SOLICITING MEMORIALS: Understanding the Need to Give in the Wake of Tragedy.

The ordeal and aftermath resulted in a giant leap forward in my self-perception as a fundraiser. I no longer saw myself as simply working in the area of philanthropy, I WAS A PHILANTHROPIST (literally, “lover of mankind”). It wasn’t because I made a donation that put me in an elite category in the donor database. It was the result of a new life orientation—like the balance had suddenly shifted. I began to identify with the mission of that children’s hospital more than I did the process of raising money for them. My personal mission is very much a part of who I am and how I see myself.

Our self-perception as career fundraisers has a lot to do with our fundraising success. The next time someone asks what you do, you can answer as you always do, “I’m a fundraiser for XYZ nonprofit.” Or you can try this response: “I’m a philanthropist championing causes of people in great need.” I like the sound of that because it fits how I want to see myself as a fundraiser.

It’s hard but essential that you remain optimistic about the future. The best antidote for fundraiser fatigue is a renewed passion for the institutional mission and the people it serves, as well as a renewed belief that most donors are still onboard and enthusiastic about future giving commitments.

Eddie Thompson founded the unique Thompson & Associates process in 1996 (then, under TrustMark Charitable Strategies) and later incorporating as its own entity in 2005. As CEO of Thompson & Associates, Eddie provides leadership and direction to over 35 seasoned charitable estate planners with an inspiring sense of generosity, integrity and passion for helping others.

Eddie serves as the Chair of the Charitable Estate Planning Institute, a 501(c)(3) public charity offering top level education on charitable estate planning for development staff, gift planning officers and professional advisors.

Strategic Philanthropy: Thinking Big in Light of Biden’s Proposed Tax Plan

By Eddie Thompson

While there are certain to be numerous negative tax implications for the wealthy under the Biden Administration, the other side of the coin is the compelling motivation to give. In other words, if donors with considerable wealth do not give away a much larger portion of their assets, the government will take those assets by virtue of the all-but-certain changes to the IRS statutes.

My advice to nonprofits in the wake of Covid-19 and the coming Biden tax changes is to think bigger and not smaller. Continue reading on how to create an organizational sea change as well as even larger gifts that will impact society as a whole (i.e. greater than your own organization).

____________

Fundraiser Fatigue:

Maintaining Romanticized Optimism About Your Profession

By Eddie Thompson

In my many discussions with fundraisers over the last nine months, one of the most frequent comments has been: “We’re so weary of talking about the Covid-19 pandemic and its ongoing impact on charitable giving.” That underlying anxiety (spoken or not) is magnified not only by the resurgence of positive tests and hospitalizations but by the uncertainty of when (if ever) things will return to a normal fundraising environment.

Among the best fundraisers, it’s not so much related to job security but to the constant frustration about their inability to do the things that they know will help fund the organization. They are, of course, concerned about their own financial security for their families, but not far behind is their passion for the institutional mission. Most fundraisers are mission-oriented, championing the cause of those in need.

The good news is that in my conversations with major donors, generally speaking, donor fatigue is far less prevalent than the corresponding fundraiser fatigue. There may be some who are hesitant to charitable giving, but the vast majority are as enthusiastic as ever about the organizations they have traditionally supported. In fact, estate-planning conversations with major donors show even greater interest in planned giving.

The good news is that in my conversations with major donors, generally speaking, donor fatigue is far less prevalent than the corresponding fundraiser fatigue.

Development professionals are on the front lines, standing in the gap for the needs of people in our communities. I’d like to encourage those who have chosen the noble occupation of fundraising with the thoughts that follow.

NOBLE OCCUPATION

The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was published in 1606. The Spanish classic follows the adventures of a nobleman who (under the assumed name, Don Quixote) set out to revive chivalry, bring justice to the oppressed, and right the many wrongs of his day. In the story, people typically made fun of Saavedra’s fictional hero because he didn’t see the world as they saw it. Don Quixote perceived himself as a man on a mission, a knightly quest to become the champion and defender of all who were in need.

The most effective nonprofit leaders I’ve known are those who have been able to maintain a kind of romanticized ideal about their occupation. That’s not always easy to do. Many at-risk kids are overcome by their risk factors, and the dreams of promising students don’t always come true. Contending with unrelenting needs as well as the occasional setbacks over time can wear down one’s enthusiasm. Nonetheless, the best fundraisers somehow find ways to remain optimistic and idealistic. In other words, the best fundraisers have a little bit of Don Quixote in them.

One of our associates told me about a similar individual—a chaplain at a juvenile correctional institution where he once worked. The chaplain was one of those irrepressibly optimistic leaders. In contrast, many of the institutional staff had grown cynical after a few years of working with kids with long criminal records and habits that were hard to break. Like Don Quixote’s critics, the correctional officers frequently made fun of the chaplain’s teary-eyed compassion and (what seemed to them) his irrational optimism.

I’ve known many great fundraisers over the years. Two from Iowa come to mind.

Charlie Becker founded Camp Courageous, an amazing summer camp near Monticello, Iowa, that serves special-needs children and adults. These individuals and their families face significant challenges every single day. Go on a tour with Charlie, and he would still tear up telling you about Camp Courageous. It was hard to resist his passion for the people he served. Charlie is now retired but as passionate as ever about the mission of Camp Courageous.

Don Ireland-Schunicht has been at the same children’s hospital in West Des Moines for 40 years. When he starts talking about what they do for patients, you get that same feeling. He’s on a life mission, championing the cause of kids facing serious medical issues. Don tears up sometimes also, but being a great fundraiser is not about tears. These two guys are much more than fundraisers. They’re fully engaged with their own noble causes.

The irony is that these men seem to be more focused on the mission than on the money, the result being that donors line up to give generously.

SELF-PERCEPTION AS A CAREER FUNDRAISER

Nonprofit executives (fundraisers in particular) are constantly making the case for their organization’s mission. If you do something enough, it’s hard to keep from becoming quite good at it. However, as a career fundraiser, the first and most important case is the one you make to yourself. Have you convinced yourself of the worthiness of your cause and career choice? Do you believe it’s important enough to put yourself out there in the role of a solicitor, constantly asking people for money? If you don’t make that case and win that argument with yourself (and win it convincingly), there will be a ceiling to how successful you can be in this line of work. That’s as true for seasoned veterans as it is for rookies.

It’s easy to feel good about yourself when your occupation is being validated by enthusiastic donors throwing money at you. However, somewhere buried in the recesses of your mind, there may be an unresolved issue. Deep down there lurks an image of yourself as a beggar on the street corner with cup in hand. It’s in hard times when that inner image begins to reveal itself—like when your ten best donors are unmoved by your latest appeal and show signs of losing their excitement for your organization. It’s in the face of those difficult situations that a weak case for the value of your occupation begins to surface. That’s when you have to fight the battle of self-perception. If that’s your situation, never give into becoming one of those task-oriented cynics like the chaplain’s critics at the juvenile correctional institution.

As a career fundraiser, the first and most important case is the one you make to yourself. Have you convinced yourself of the worthiness of your cause and career choice?

A GRADUAL PROCESS

If I believe in a cause and have properly cultivated the relationships, I have no hesitation about asking donors to give with extreme generosity. But that wasn’t always the case. At the beginning of my career, it was inconceivable to me that people would make the kind of donations that I now see regularly. With time and experience, my confidence grew, and I got much better at asking for money. However, a seminal moment in my own professional development came with the loss of our infant grandson and my own son’s subsequent challenge to me. See SOLICITING MEMORIALS: Understanding the Need to Give in the Wake of Tragedy.

The ordeal and aftermath resulted in a giant leap forward in my self-perception as a fundraiser. I no longer saw myself as simply working in the area of philanthropy, I WAS A PHILANTHROPIST (literally, “lover of mankind”). It wasn’t because I made a donation that put me in an elite category in the donor database. It was the result of a new life orientation—like the balance had suddenly shifted. I began to identify with the mission of that children’s hospital more than I did the process of raising money for them. My personal mission is very much a part of who I am and how I see myself.

Our self-perception as career fundraisers has a lot to do with our fundraising success. The next time someone asks what you do, you can answer as you always do, “I’m a fundraiser for XYZ nonprofit.” Or you can try this response: “I’m a philanthropist championing causes of people in great need.” I like the sound of that because it fits how I want to see myself as a fundraiser.

It’s hard but essential that you remain optimistic about the future. The best antidote for fundraiser fatigue is a renewed passion for the institutional mission and the people it serves, as well as a renewed belief that most donors are still onboard and enthusiastic about future giving commitments.

Eddie Thompson founded the unique Thompson & Associates process in 1996 (then, under TrustMark Charitable Strategies) and later incorporating as its own entity in 2005. As CEO of Thompson & Associates, Eddie provides leadership and direction to over 35 seasoned charitable estate planners with an inspiring sense of generosity, integrity and passion for helping others.

Eddie serves as the Chair of the Charitable Estate Planning Institute, a 501(c)(3) public charity offering top level education on charitable estate planning for development staff, gift planning officers and professional advisors.

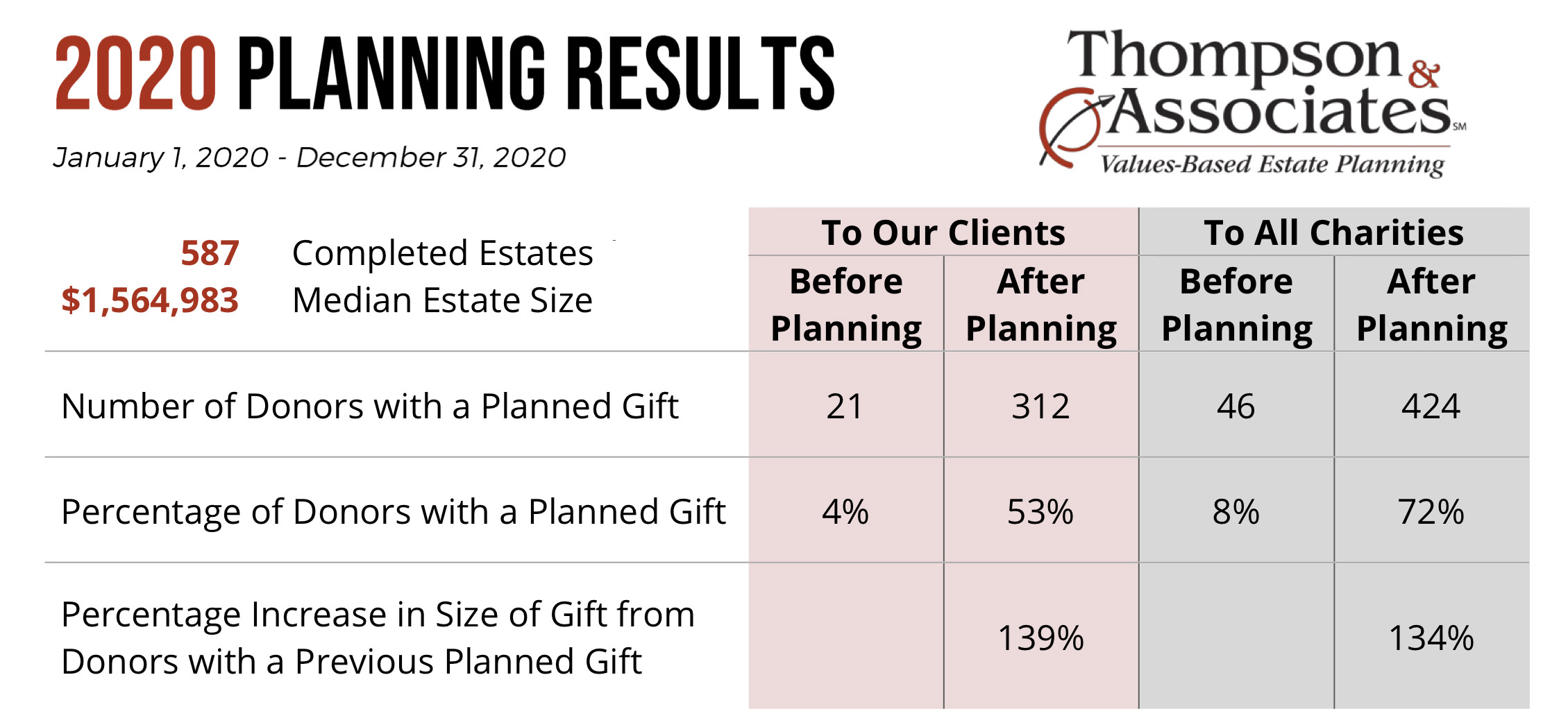

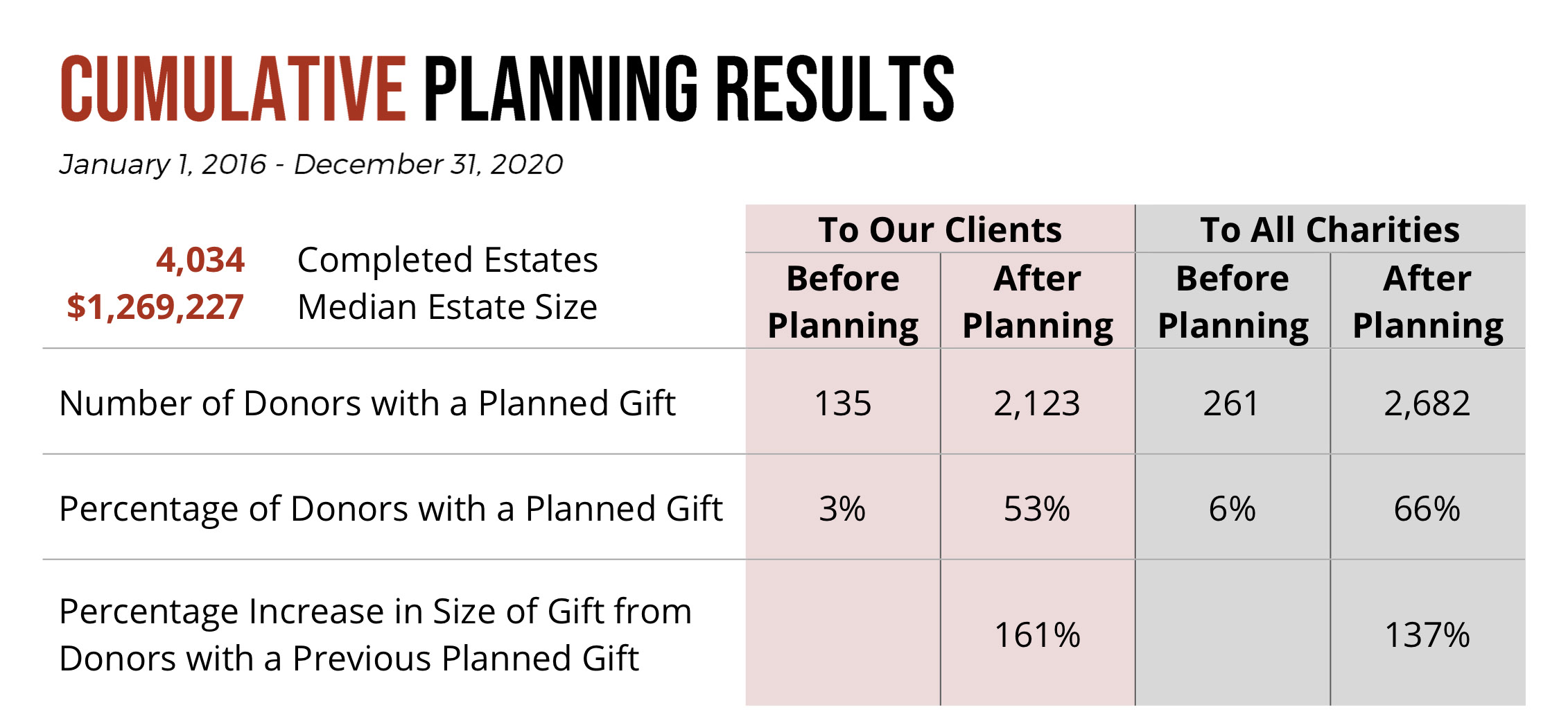

Even amid the pandemic, we continue to be encouraged by the part we’re able to play in facilitating charitable gifts through the Thompson & Associates foundation-sponsored estate planning process. We are proud of what we’ve been able to do for our clients, but that’s really not the point here. Rather, it’s the

Even amid the pandemic, we continue to be encouraged by the part we’re able to play in facilitating charitable gifts through the Thompson & Associates foundation-sponsored estate planning process. We are proud of what we’ve been able to do for our clients, but that’s really not the point here. Rather, it’s the